Coast Out to Coast In

Coast out to Coast In

aNATomy of a NAT Flight Part 2

Coast out to Coast In

In our last post, while in Flight Ops, we prepped for our Atlantic transoceanic flight from JFK (New York) to LHR (London).

Now, it’s time to make the donuts!

After liftoff from JFK, we crossed a swath of eastern Canada, and approached the Atlantic coast somewhere in the vicinity of Gander.

Before we can go “feet wet” over the Atlantic, however, we still need one last crucial piece of paperwork: the Oceanic Clearance.

Coast out to Coast In

The Oceanic Clearance

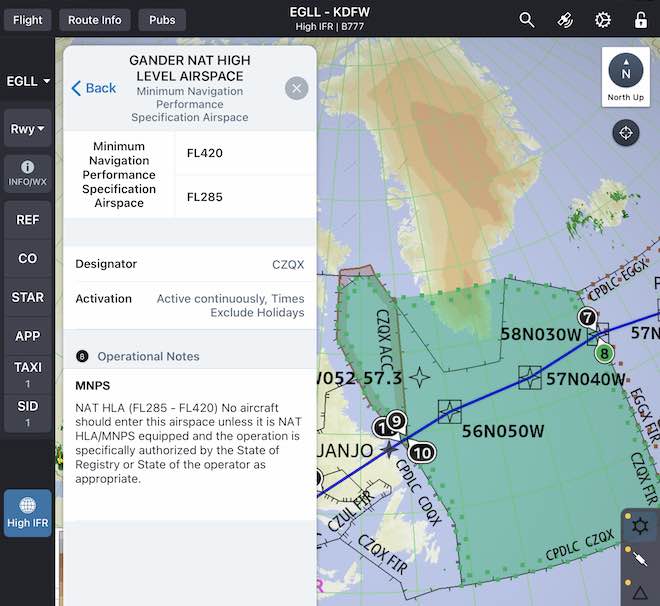

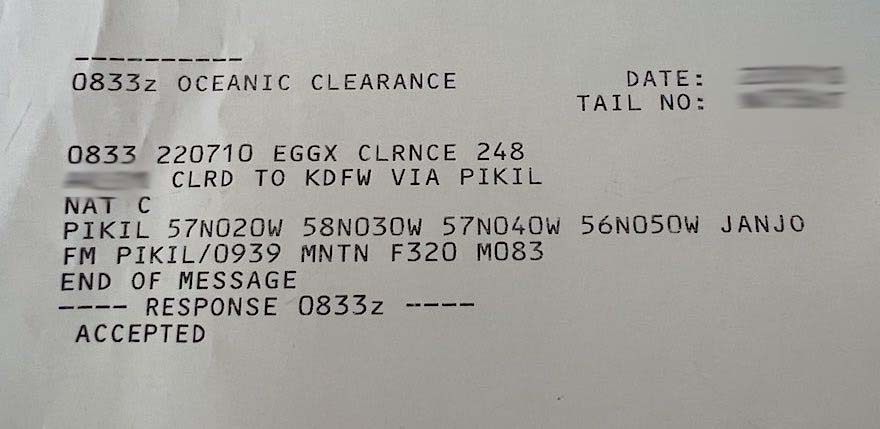

As we learned in our last post, despite the fact that we do indeed have our main clearance from Point A to Point B, we still need a specific, and separate, clearance to fly our Atlantic track.

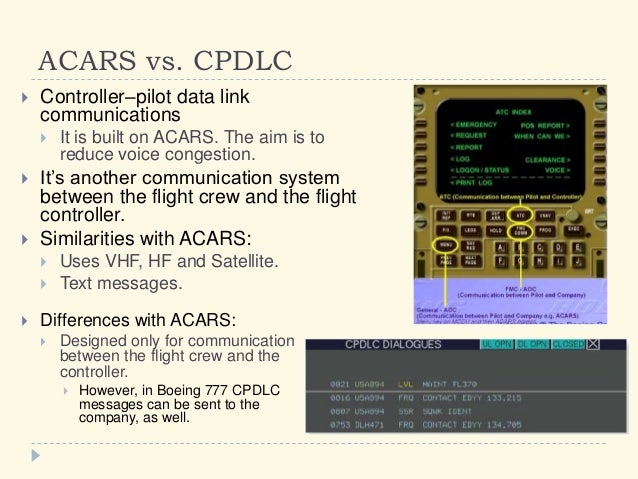

Time to activate the CPDLC and login with Gander Oceanic.

Once communication is established via CPDLC (think of it as an elaborate texting system), we’ll request our clearance. While the ATC system already has our requested route on file, now that we’re approaching the Oceanic Boundary, we need to request from them the specifics, based on actual traffic:

- Route—Specifically, the oceanic entry point. (In the sample above, “JANJO”)

- Entry Point ETA

- Requested Flight Level (Altitude)

- Requested Mach speed

- Any other requests, such as “able a higher flight level”

First, we’ll get a “Stand by” message acknowledging our Oceanic Request.

Then, we sit back and bite our nails.

Will we get it in time?

What do we do if not get the clearance in time?

While we will continue to fly the original flight plan regardless, our clearance could come back modified. In this case, we could launch out over the Atlantic on the wrong track, thus generating…

Coast out to Coast In

The "Gross Navigation Error"

Every Oceanic pilot’s dread is to generate a “Gross Navigation Error” (GNE).

While we always strive to fly on course (of course!), most of the time while flying in the States and Canada, we’re in positive radar contact. We can request shortcuts, deviations for weather, etc.

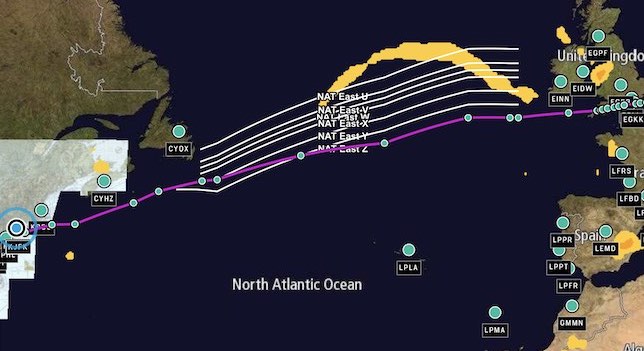

Over the Atlantic, however, we will mostly be out of radar contact. While GPS and ADS-B has mostly overcome the non-radar disadvantage, maintaining the expected course, altitude and speed becomes hypercritical.

VHF, HF & SelCal

Another critical factor is communication.

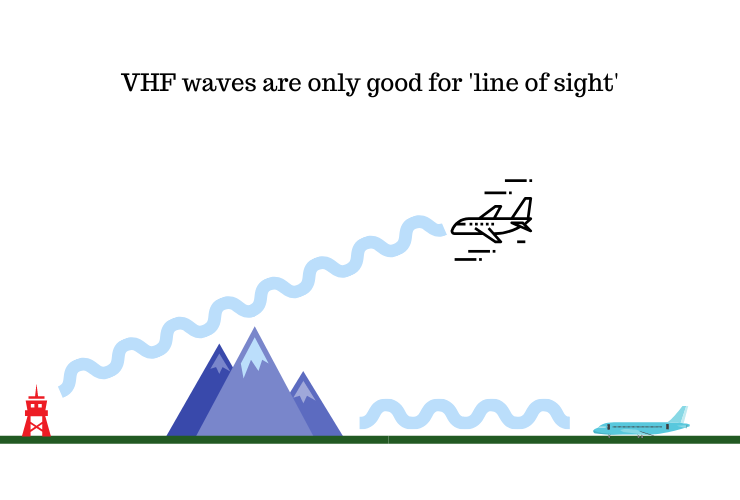

Again, in the States and Canada (basically over land), we will be in constant radio contact with ATC via VHF frequency. However, VHF is limited to line-of-site. Out over the Big Blue Ocean, we’ll be a long way from “Land Ho.”

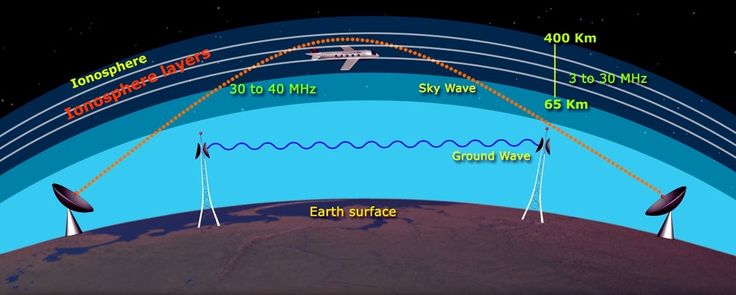

As a backup, we will switch to a lower frequency band, HF, which does allow long range communication. However, this band is notoriously scratchy, obnoxious to hear, and unreliable. A radio operator’s voice will fade in and out, increasing difficulty to communicate.

In fact, the best frequencies change from hour to hour, based on location and atmospheric conditions.

So, to be “fer sure fer sure,” before we sign off of the more reliable VHF frequency, Gander Radio will assign us two HF frequencies, a Primary, and a Secondary. With a little luck, if one doesn’t work, the other will.

Then, we’ll switch over to our HF radio, check in with Gander Oceanic Radio on HF, and request a SelCal (SELective CALling System) check.

“Gander Radio, (call sign) on frequency 5298, requesting SELCAL check, over.”

Typical SelCal Check

Basically, this SelCal check is a “phone call” via HF, which will “ring” the cockpit if needed. If the system works, there will be no need to monitor the annoying HF frequency.

So, out over deep waters, we’ll have at least two functioning communication systems: CPDLC, and HF.

Again, the HF frequencies are a backup to our primary mode of communication, the CPDLC. As long as we got a “phone call” from Gander via CPDLC, we won’t have to actively monitor the (obnoxious) HF frequencies.

Think flying across the Atlantic is exciting?

Check out Cap’n Aux’s other adventures—from 3 (no, make that 4!) decades in the sky!

Four volumes from Three decades of adventures in the sky!

- Cap’n Aux’s Adventures

- Contributing Pilots’ Adventures

- Photos

- Links to other cool stuff!

Click on the link above for a free preview!

Coast out to Coast In

Capn's Log, Stardate...

Back to avoiding that “Gross Navigation Error (GNE)”…

To keep us spot on with our navigating, we will be constantly verifying our position on-course, re-evaluating our progress, and updating our prediction, if needed, to cross the next waypoint.

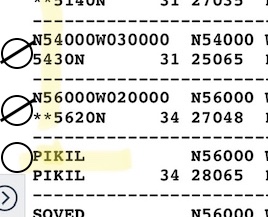

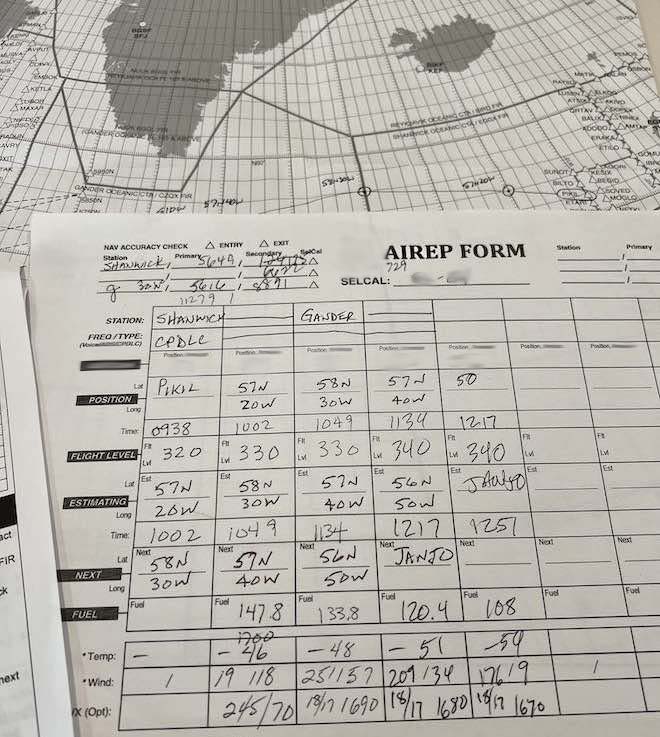

In order to do this, we’ll be using our AirRep form.

Above is an East-West AirRep form. Starting with the Coast Out waypoint of Pikil, each Lat/Long is listed across the ocean. Each point has an ETA, ATA, verified altitude, fuel check, etc.

As each point is approached, we’ll double check that we’re on course, altitude, speed, and our time to next fix hasn’t changed by more than 3 minutes. If so, we MUST advise ATC to avoid the dreaded GNE!

Also, it’s a handy time to check engine parameters and oxygen, just in case something begins to trend the wrong way.

In addition to the AirRep form, we’ll always verify the next two waypoint fixes before crossing. We’ll check the points vs. our flight plan, our cleared route, and verify that both waypoints match (nearly) exactly the:

- MC (Magnetic Course in degrees +/- 1 or 2);

- NM (Nautical Miles +/- a few)

This is yet another way to be certain we’re where we’re supposed to be, and where we’re supposed to go.

Coast out to Coast In

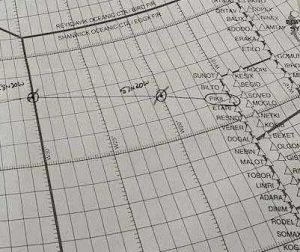

Circle and Tick

Finally, as we go, we’ll “Circle and Tick” off these verifications, on either our hard copy of the flight plan, or our elde-fashioned chart.

(See below—By the way, the two pics below are from two different flight plans, both which happen to Coast In at Pikil. No GNE’s for us today!!)).

If all goes well, we’ll Coast In at our pre-planned waypoint (Pikil, in the examples above), and at the preplanned time and altitude.

Then, we can breathe a slight collective sigh of relief, and continue on our merry way to destination.

While Cap’ns Kirk and Picard might not get “Lost in Space” (very often), it’s up to us transoceanic pilots to make dang sure we never, ever, ever do!

Hemisphere Dancing Report

The Mighty K2!

More Himalaya Dancin’!

Recently, I picked up another DEL trip, this time as Relief Captain. On my shift, we flew yet again over the western portion of the Himalayas. It was particularly clear that day, which afforded a spectacular view!

While it was more clear than normal, it wasn’t quite “CAVU” enough to spot K2, which was 200 miles to our East. Fortunately, a recent FO of mine did get to see it on one of his trips. Check this out!

Hemi Dancin' Bonus!

On my next trip, I commuted to base by jumpseating on a 787. What a sweet ride!

And, I must admit: I’m kinda jealous of those dope HUDs they got!

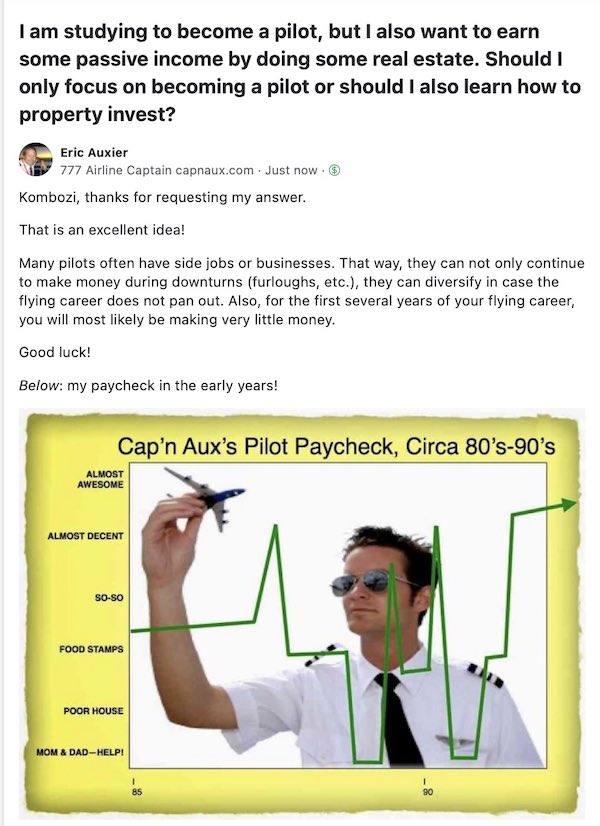

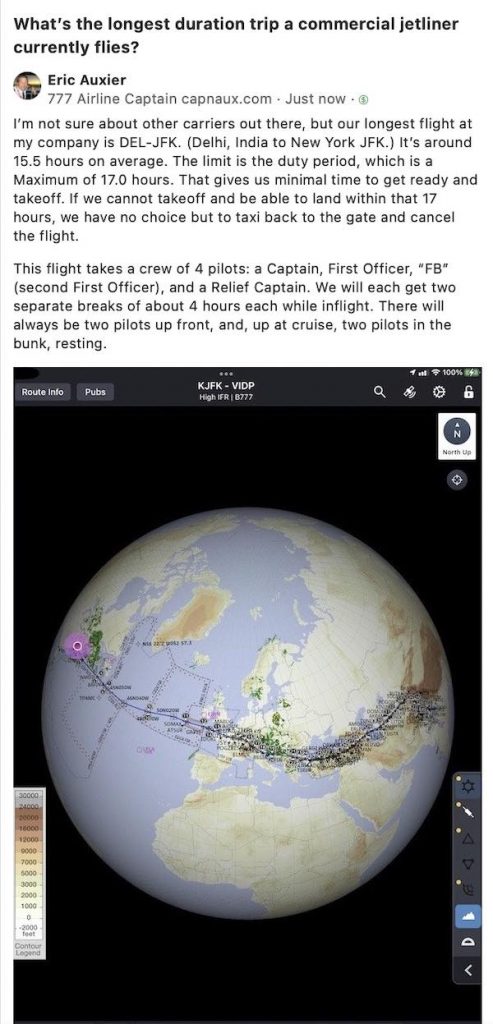

Quora Question Quorner

Wherein I answer some of your favorite questions in Quora’s aviation forums.

Come over and join us at:

Flying for Dollars!

Flying for Love!

Till the next post,

This is Cap'n Aux

Signing Off!

Cleared to Land

Touching Down Next

aNATomy of a Polar Flight

Taking Santa's Shortcut

Cap'n Aux Social Media Links

- Books: Amazon.com

- Email: eric@capnaux.com

- Facebook: CapnAux

- Twitter: @capnaux

- Instagram: @capnaux

- Quora: CapnauxSpace

Related Links

- aNATomy of a NAT Flight Pt. 1 https://capnaux.com/anatomy-of-a-nat-flight

- Of ETOPS, NATs and SLOP https://capnaux.com/of-etops-nats-and-slop/

- Of RAIM, ADS-B and CPDLC https://capnaux.com/of-raim-ads-b-and-cpdlc/

- Diverting to Alternate! https://capnaux.com/diverting-to-alternate

- Inflight Medical Emergency! https://capnaux.com/welcome-aboard-passengers-part-ii-medical-emergency/

- A Passage to India Part 1 https://capnaux.com/a-passage-to-india-part-1

- Life of an Airline Pilot:

- A Month in the Life of Cap’n Aux https://capnaux.com/a-month-in-the-life-of-capn-aux/

- Bid Life of an Airline Pilot https://capnaux.com/the-bid-life-of-an-airline-pilot/

- Life as a Reserve Pilot https://capnaux.com/life-as-a-reserve-pilot/

- Life as a Reserve Commuter Pilot https://capnaux.com/life-as-a-reserve-commuter-pilot/

- Top 10 Downers of an Airline Pilot Career https://capnaux.com/top-10-downers-of-an-airline-career/

- An Airline Pilot Retires https://capnaux.com/an-airline-pilot-retires/

- Life of a Test Pilot https://capnaux.com/the-occasionally-exciting-life-of-a-test-pilot/

- The Making of a European Pilot https://capnaux.com/the-making-of-a-european-airline-pilot/

- Confessions of a Former Airline Pilot https://capnaux.com/confessions-of-a-former-airline-pilot/

- 777 Adventures

- Hemisphere Adventures! https://capnaux.com/hemisphere-adventures/

- Dancing the Hemispheres https://capnaux.com/dancing-the-hemispheres/

- Maiden Voyage of the Boeing 777 https://capnaux.com/maiden-voyage-of-the-boeing-777/

- Getting Certified on the Boeing 777 https://capnaux.com/whats-it-like-to-get-certified-on-one-of-the-worlds-largest-airliners-the-boeing-777-type-rating/

- Drinking From a Firehose Part 1 https://capnaux.com/drinking-from-a-firehose-part-1/

- A Quora Aviation Q&A Quorum! https://capnaux.com/a-quora-aviation-qa-quorum

- Cap’n Aux Answers Your Avgeek Questions

- Part I https://capnaux.com/capn-aux-answers-your-avgeek-questions-part-i/

- II https://capnaux.com/capn-aux-answers-your-avgeek-qs-part-ii/

- III https://capnaux.com/capn-aux-answers-your-avgeek-qs-part-iii/

- IV https://capnaux.com/capn-aux-answers-your-avgeek-qs-part-iv/

- One Final Q! https://capnaux.com/interlude-vlog-one-final-avgeek-question/

- Airbus Adventures

- Fifi’s Final Flight! https://capnaux.com/fifis-final-flight/

- Cap’n Aux’s First Solo https://capnaux.com/blogging-in-formation-solo/

- End of an Aviation Era https://capnaux.com/end-of-an-aviation-era/

- A Tale of Two Upgrades https://capnaux.com/a-tale-of-two-upgrades/

- As the Turbine Turns https://capnaux.com/as-the-turbine-turns/

- Cap’n Aux Vimeo Page https://vimeo.com/capnaux/

- All Word on the Ramp Videos https://vimeo.com/manage/showcases/3162370/info

- Best of Videos https://vimeo.com/manage/showcases/3162373/info

- Fun Stuff and Best of Cap’n Aux

- Top 10 Things to Never Say to a Pilot https://capnaux.com/top-things-never-to-say-to-a-pilot/

- The Airline Cockpit in 7 Steps https://capnaux.com/airline-cockpit-7-steps-updated/

- Top 10 Downers of an Airline Pilot Career https://capnaux.com/top-10-downers-of-an-airline-career/

- Black Swan Event Part 1 (Video Interview with Qantas A380 Captain de Crespigny) https://capnaux.com/black-swan-event-the-captain-de-crespigny-story-pt-1/

- WOTR Video: It’s What Pilots Do! https://capnaux.com/word-on-the-ramp-video-its-what-pilots-do/

- Pilots of the Caribbean https://capnaux.com/there-i-wuz-pilot-of-the-caribbean/

- Part 2: Stranded in Paradise https://capnaux.com/pilot-of-the-caribbean-part-2/

- Life in the Sky with Covid

- Pilots Protest Covid Mandates https://capnaux.com/pilots-protest-covid-mandates/

- The Post-Covid Future of US Aviation https://capnaux.com/the-post-covid-future-of-u-s-aviation/

- Flying in the Age of Covid https://capnaux.com/flying-during-covid/

- Lessons From the Miracle on the Hudson https://capnaux.com/forced-landings-pilot-lessons-from-the-miracle-on-the-hudson-part-1/