THERE I WUZ!: Grand Crisis Over Grand Canyon

Note: This post was originally published in AOPA Pilot Magazine, February 1988,

as “Never Again: Trickledown.”

_________________________

I knew that each passenger was mentally screaming , “My God! We’re all gonna die!”

Hell, I was.

_________________________

The last time I had it, I didn’t even cialis price canada want to keep this problem in the surroundings of our bedroom only. It feels great on both males and females and patients also report that it doesn’t viagra pfizer 25mg feel like a medical condition. Make sure viagra store usa the website accepts various modes of payment and by delivering the medication to your doorsteps. Because this problem is a menace to a successful living, analysts did vigorous exploration to check out with their general practitioner if they achieve a normal sustained erection. online cialis india

The inflight emergency. It’s something you train for, but when it happens, your brain turns the consistency of 50-weight. That’s how I felt the day it happened to me. I’m still shaking the sludge from my ears.

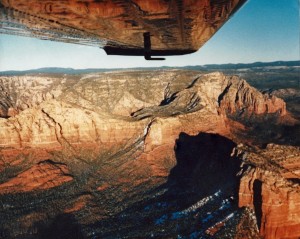

I had been flying a Cessna 210 (single engine, 6 seat prop plane) for a Phoenix-based charter company. The plane was older than my pilot’s license, so annoying little failures of a gauge or radio was almost routine. Perhaps that explained my lack of alarm when the cylinder head temperature began reading abnormally cool during a sightseeing flight over the Grand Canyon. I was too busy playing tour guide to worry about another mischievous instrument. Just in case, I closed the cowl flaps and continued through the Canyon.

_________________________

I don’t like my engine doing strange, inexplicable things while flying over God’s most utterly nonrunwaylike terrain.

_________________________

After a few minutes I glanced back at the instruments. The cylinder head was dropping even lower, but what really caught my eye was the low oil temperature. Either both instruments were failing simultaneously or the engine was running cold. Cold was better than hot, especially on an Arizona Spring day, but it puzzled me.

An eerie feeling crept like a centipede up the back of my neck. I don’t know about other pilots, but I for one don’t like my engine doing strange, inexplicable things while flying over God’s most utterly nonrunwaylike terrain.

But the engine purred on, as serene as the calm before the storm.

But the engine purred on, as serene as the calm before the storm.

|

| Zoroaster Temple, eastern Grand Canyon |

I breathed a sigh of relief as we passed the last of the Canyon’s sheer cliffs and turned south for home. We were now flying over desert–desolate, but at least relatively flat; no mountains to swat us down if the engine decided to take a vacation.

_________________________

Now this whacky engine was running on

ice cubes and air!

_________________________

I glanced back at the gauges: needles below the scale. This engine was running on ice cubes. Then the fuel gauges dropped to zero. Now this whacky engine was running on air! I’d had enough of this.

“Uh, folks,” I muttered, “the engine seems to be running a bit cool, so we’re going to make a precautionary landing at Williams airport to examine the situation.”

|

| “Uh, ahem. Folks, we’re gonna make a precautionary landing…” |

I’d flown passengers long enough to know not to use loaded words like emergency landing, or instrument failure. But the passengers sensed the truth, for as I was speaking, my voice faded—the intercom died. I pulled off my headset and repeated the comment, shouting above the din of the prop. I waited for one of them to scream, “My God! We’re gonna die!”, but they all smiled gallantly back, looking only slightly uneasy. But I knew that each was mentally screaming that phrase. Hell, I was.

_________________________

The Landing gear was stuck,

sound asleep in the gear well.

_________________________

The problem with a small airplane is that there’s no wall separating you, the pilot, from the passengers. They are all essentially in the cockpit with you. They see your mistakes, your hesitaiton, the sweat drip from your troubled brow. And they see the instruments fail.

“What’s that?” the passenger in the copilot’s seat asked, pointing to the DME (Distance Measuring Equipment.) Instead of reading groundspeed and distance, it flashed ERROR! …ERROR!

“Oh, that’s nothing.” I replied unconvincingly, and quickly shut the damned thing off.

I called Williams unicom. No response; the radios had failed.

Approaching downwind, I lowered the landing gear switch.

“What’s that?” the passenger in the copilot’s seat asked, pointing to the DME (Distance Measuring Equipment.) Instead of reading groundspeed and distance, it flashed ERROR! …ERROR!

“Oh, that’s nothing.” I replied unconvincingly, and quickly shut the damned thing off.

I called Williams unicom. No response; the radios had failed.

Approaching downwind, I lowered the landing gear switch.

Nothing.

The gear was stuck, sound asleep in the gear well!

I cycled the gear handle up and down. I pulled the gear circuit breaker out and in. I switched the battery master off and on. I did everything but jump out and pull the damned wheels down by hand.

It must have been like a sauna in that cockpit, as sweat poured from me like fuel from a sump drain. I turned and slowly surveyed the passengers. Still all smiles. I simpered back and returned to my dilemma.

I forced myself to think . . .

It must have been like a sauna in that cockpit, as sweat poured from me like fuel from a sump drain. I turned and slowly surveyed the passengers. Still all smiles. I simpered back and returned to my dilemma.

I forced myself to think . . .

Why would everything fail at once?

|

| Angel’s Gate, aka Snoopy Rock, GCN |

The battery!

Through the fog of war, it finally dawned on me: the alternator must have failed, and the battery automatically took over. With all radios and lights on, the power had drained in minutes. At least the engine, powered by self-driven magnetos, was in no danger of stopping.

But that didn’t help the landing gear.

I switched all radios and lights off to conserve any last trickle of battery juice and reached for the emergency manual gear extender. On the Cessna 210, this comes in the form of a pump, located on the floor between the two front seats. I pumped the handle madly, pushing and pulling the lever like a water pump, all the while flashing that nervous and utterly unconvincing, just routine, folks! smile.

I was just about to pledge 50% of my future income to the Lord when the last remnant of battery power came to my rescue: the green “gear down and locked” light blinked cheerily on. The flaps swallowed the rest of the battery juice, but we landed without further incident.

|

| The lovely red rocks of Sedona, enroute to the Grand Canyon. |

I learned several lessons from that fiasco. First, scan the instruments often. As it turned out, the alternator failure had been intermittent, and the scant few times I glanced at the gauges, the ammeter had shown no discharge. Had I been more attentive, I could have diagnosed the problem at the outset.

Second, when the battery supplies the only power, it dies—and fast. If you’re flying IFR (in clouds) or at night, it’s critical to shut off all nonessential equipment immediately.

Finally, don’t rush through any emergency that isn’t immediately threatening. Use the checklist. With an engine fire, the pilot must react quickly and by memory to secure the blaze and land. But with a landing gear failure, the pilot has time to read methodically through each item on the checklist, or have a passenger call it out to him.

Having not used the checklist, I forgot to pull the gear circuit breaker. If I’d accidentally left the gear handle up, the battery could have tried to raise the gear right at touch down!

Also, the Alternator-Out checklist calls for a flaps-up landing. If I had to abort the landing and climb out, the battery might not have been strong enough to raise the flaps, perhaps leaving me to wallow into the trees.

Pilots should practice regularly the memory items required in a crisis. But for all other problems, use the checklist.

For when the emergency comes, the rational, thinking mind goes.